By Abel Akara Ticha

As the world trudges through the global food chain crunch, which has already triggered violent protests in Africa – with Sierra Leone topping the casualty charts, children, especially those of school going-age, are bearing the brunt.

Given the situation at hand, I found it most tempting to highlight the plight of school-going children (to whom school meals are vital for physical and mental development) by revisiting school feeding practices of my childhood in a corner of Africa, connecting it to the current situation and showcasing an example of what I will call ‘agripreneurship’ which can hopefully provide some enlightenment.

Brunch time at my primary school – the Catholic school, Small Soppo in Buea in Cameroon in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s was characterised by bullying, counter-bullying, scrumping for food, and portion-bites-for-football trade-offs.

The main meal break was from 11 am to noon and that was the only time we were allowed to munch on anything at school. With no free brunch provided, we had to choose from three celebrated eateries:

1. The ‘dining shed’ where women from the Small Soppo neighbourhood sold simple pre-cooked dishes such as rice and beans, rice and stew, and corn chaff. Rice was the staple.

2. Mami Ambe’s – a joint near the northern edge of the school. Mami Ambe was married to the chef of the Bishop of the Buea Catholic Diocese (which owned our school). She made finger-licking tasty dough fritters called achombo.

3. Mami Yvonne’s. This was the home of another woman, whose husband worked for the Catholic Mission. They lived at the southern edge of the school, bordering Bishop Rogan College. She also made achombo.

The price for meals (such as rice and beans) ranged from XAF25 (25 CFA Francs) to XAF100 a plate (XAF100 is slightly less than 20 US cents today). That was a huge sum for pupils to get hold of. Not everyone could afford to splash out XAF50 or XAF100 a day for a meal so, developed a buddy system. You shared the meal with your buddy on Monday and he returned the favour on the next day and so on for the rest of the school week.

But school bullies were not part of this arrangement but the insisted on being part of the spoils. These were usually older boys. They would approach you while you were at your plate and ask: “I chop? I chouk? I lick?” (Pidgin for “Just a bite? A dip-in? A taste?”).

You often did not have a choice but to give in, in which case the bully would scoop out a bite, then move on to his next victim, till he had eaten his fill from his buffet round. If you said no, your plate would be flicked off your hands and its content splattered on the rough floor.

You did not have much of an avenue for recourse unless you had an older brother who was indeed a bigger bully. In such a case, he would settle the matter after school hours, administering a painful lesson on the junior bully via copious blows. Despite this dog-eat-dog system, junior bullies still took the risk of venturing into dangerous waters from time to time since I Chop, I Chouk, I Lick practice seemed to haveossified in their psyches.

Achombo

These cost XAF25 for the smaller dough cake and XAF50 for the bigger version. Pupils who had only XAF50 for their meal preferred the bigger option as it filled one’s stomach nicely. One sweet big cake from Mami Ambe and some tap water did the trick!

Mami Yvonne was the specialist of the smaller achombo which cost XAF25. Hers were a little saltier but she had her faithful clients too.

Achombo was a practical, handy snack, so pupils could bring it to class (while still on their brunch break) and eat freely to the envy of those who could not afford to get the cake that day. Like the leader of a pack of dogs, the eater would be surrounded by less privileged puppy-eyed mates. The presiding star would cut a few, less-than-bite sizes bits to offer the salivating onlookers.

Given that the ‘affordability pendulum’ could swing the next day, some eaters were a bit more generous in anticipation of their own rainy days. But there were pupils whose fountain flowed every day, on account of their parents’ wealth.

Some pupils, especially girls, were wise and frugal enough to save up for weeks or months, in order to buy packets of candies, which they retailed illegally to other pupils. That way, the profit went into their achombo taps which never ran dry.

Some boys who did not get sufficient food money but owned footballs, would strike up priceless bargains, exchanging bites from those who had the food for the privilege of being picked to play in a team during the break.

The school compound in the Catholic mission was very big, with two football pitches, a handball pitch and some open spaces where make-shift soccer games took place. Pupils even had access to an open basketball court of the neighbouring Bishop Rogan College, which was less frequently used by the students of that junior seminary.

Stealing from Bishop Rogan College orchards

The Bishop Rogan College Small Soppo, had some impressive orchards where bigger and more courageous boys ventured to steal fruits for break time and after-school snacks. Their scrumping worked most of the time. But, as the saying goes, 99 days for the thief, one day for the owner. I witnessed the mass thrashing of some of these big boys at school whenever they were rounded up with their loot from those orchards. No matter how painful the flogging, which were held urbi et orbi, proved to be, the culprits collected themselves and continued with their credo – a luta continua.

from Catholic School Small Soppo to the world

This story of the differing fortunes in accessing meals at school during my formative days in the early 1980’s is an indication that even when things looked good in the era of the Green Revolution in Cameroon, the majority of people faced some degree of food insecurity, which affected the study life of their children at school.

With the passage of time, matters only seem to worsen as more and more people (in absolute numbers) have become food insecure, which means they are grimly unsure how they can afford or access food in the foreseeable period.

In its 2021 report The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World the FAO revealed that between 720m and 811m people faced hunger in 2020. Currently, according to the Nobel Peace Prize winning WFP, up to 345m people in 82 countries face acute food insecurity with 73m primary school children going hungry while on campus.

One of the myriad ways in which WFP has been leading global efforts to structurally assuage the problem is through its school feeding programme through which it catered for 15m children at school in 2020. The UN food relief agency has even partnered with like-minded bodies to form the country-led School Meals Coalition which supports school children in 60 countries.

The UN bodies mentioned above are conscious of the fact that although creating and maintaining safety nets for the vulnerable is a good measure to tackle hunger and food insecurity, better production and distribution systems are the long-term keys to solving the problem especially in weaker economies. In these countries, structural transformation especially in agribusiness would result in wider food availability and affordability.

African brains at work

The case has been abundantly made for governments to support entrepreneurs of the mass production and distribution of processed food items that are locally popular and have high nutritional value.

One such is Dr Emmanuel Fon Tata of AfroBrains Cameroon (ABC). This versatile engineer who was highly sought-after by Chinese firms, returned to Cameroon to set up a world class food processing factory in Yaounde.

As if he had foreseen the Covid-induced disruption of global food supply chains he devised ways of enriching flour from homegrown tubers such as cassava to render it 100% ready for pastry. He also produces first rate cooking oil from groundnuts grown in Cameroon.

His model is to provide farmers with skills and the best inputs to produce quality organic food and animal breeds, help them with engineering support to mechanise and automate some of their processes, and ultimately buy back the harvests from them for transformation and marketing.

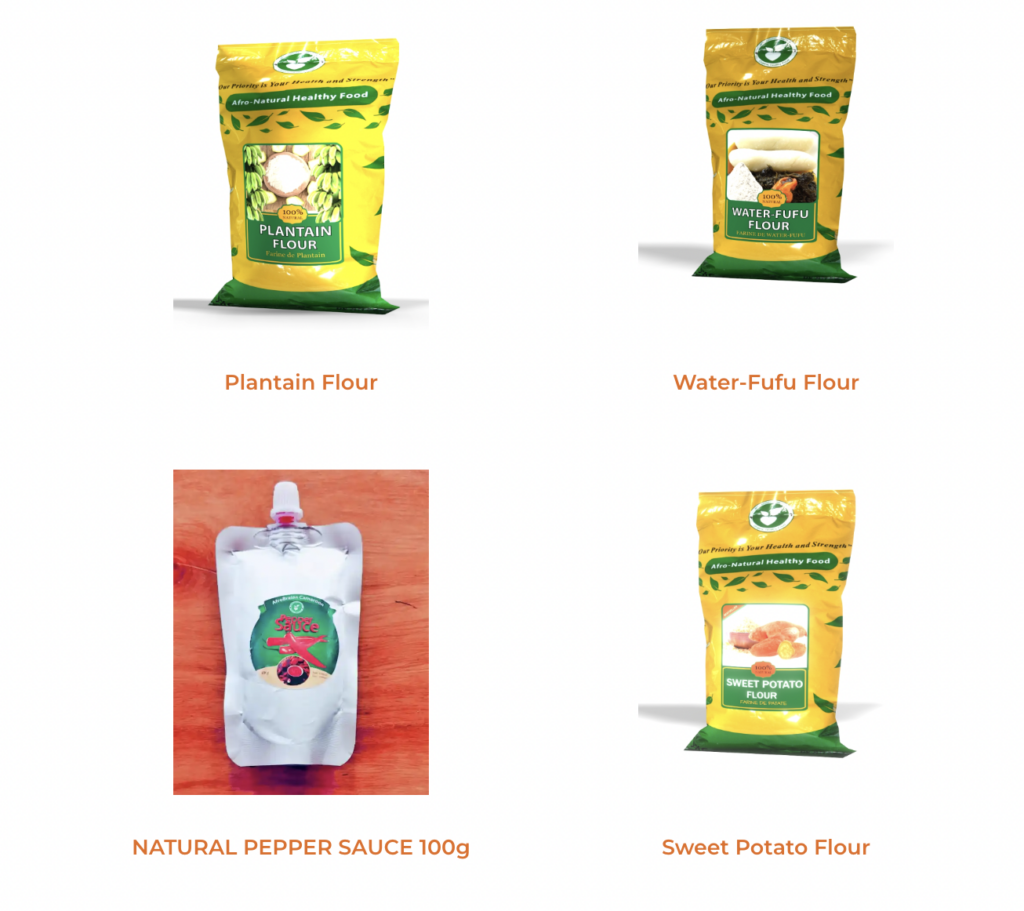

This creates a good number of direct and greater number of indirect jobs. Aside from satisfying the tastes of Africans for vegetable oil, pastry and pasta, he is packaging traditional staples such as water fufu flour (from cassava), achu flour (from colocacia) and plantain flour in formats which maintain their organic and aesthetic goodness to make cooking easy for today’s busy lifestyles. His firm already has 24 products on the market ranging from the flours to peppers and tomato puree.

“We do not use any additives or artificial colouring on our products,” he says, “we scan all our raw materials to make sure they are not genetically modified, and we rather encourage our farmers to use the hybrid seeds of the Agricultural Research Institute for Development (IRAD) as they are not GM seeds. GM seeds are not only less healthy but are unsustainable.”

This organic approach is working as local and diaspora demand massively outweighs current production capacity. There are two main hurdles here – the limited supply of inputs and the shortfall in electrical energy for manufacturing.

To the first problem, Dr Tata is on a campaign to encourage government to help groundnut farmers in the northern regions of Cameroon to produce more and channel them to local processors up the value chain like himself to spin into cooking oil. This, he contends, is one sure way of beating dependency on the importation of cooking oil.

At the moment, due to global supply chain disruptions, partly linked to the crisis in Ukraine, the price of oil has shot through the roof in Cameroon, like elsewhere in Africa, prompting government to try the palliative approach of buying off stock at their high selling prices and retailing to communities in big cities at subsidised rates.

“This approach helps but is not sustainable,” he contends, as “neither can it be done for long, nor can it benefit more than a handful of people.” If he (and others in the sector) can get enough supply of cassava and investments to expand his processing plant, flour-ready-for-baking should become once more fully accessible on the local market at good prices. Humans shall not bake by wheat alone!

To tackle the energy insufficiency problem, he is developing a project to use biogas as a by-product of waste matter within his own forward and backward agro linkages. He hopes to generate 60KWh of energy to run part of his operations.

As Dr Tata and other Africans agribusiness entrepreneurs fly the agribusiness flag high, they need support from authorities as well as investments. For, what they are doing is pivotal not only in the import-substitution of crucial staple foods, but for ensuring local food security and paving the way for value-added food exports.

When they do make a breakthrough, lunch time meals for primary school children in schools such as the Catholic School Small Soppo which we saw at the start of this article, and elsewhere in Africa, would no longer be a privilege but a right.

Beautifully count on the early stage of our humble lives as African children with nearly a mean to have a descent feeding routine .

Beautifully write up Sir

Very many thanks, Eric!