By Abel Akara Ticha

I) Introduction

Among the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which morphed out of a rather checkered bid by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to transform the world by 2015, SDG 13 (“take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts”) is key. A prima facie look at the Goal’s five targets and eight indicators, would comfort the observer that it is crafted to reverse the anthropogenic contributions to a dangerous warming of the earth, commenced during the industrial revolution and aggravated at the cusp of the 20th century (see Gough, 2017; Klein, 2015; Skillington, 2017). However, in critically evaluating both the well-intentioned template of SDG 13 within the framework of Agenda 2030; and global commitments to stop greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (which cause global warming and its associated dramatic weather events) it is observable that the current world structures dominated by neoliberal extractivism and profiteering in the Global North have squashed hopes of resolutely mitigating climate change by 2030.

As a contribution to the broader process of evaluating the SDGs, this article examines the capacity of the machinery around SDG 13 to transform the world by 2030 from a mixed bag of critical theories and notions.

These include Environmental Justice and what Edward Said (1979, in Dawson, 2013) qualifies as the counteraction of Imaginative Geographies in the world order.

II) Raison d’être, political and socioeconomic context of SDG 13 and evolution from MDG 7

SDG 13 was borne out the need to recalibrate global development on a sustainable path which “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (United Nations, 1987, p. 15). The first international admonition on “the serious probability of climate change generated by the ‘greenhouse effect’ of gases emitted to the atmosphere” was made by the Gro Harlem Brundtland-led Report (United Nations, 1987, p. 121). It warned of the risks of the destruction of the environment manifested in desertification, deforestation, toxic wastes, and acidification, climate change, ozone depletion, and species loss, in ways that were “faster than do our abilities to manage them” (ibid).

The Brundtland Report built the momentum for the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in June 1992 which opened up for countries’ signature, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Dasandi, et al., 2015). The Convention set the standards for an international response to climate change, notably that global GHG be reduced by 60% on threshold of the 21st century (Skillington, 2017). However, by 1995 it was evident that the modus-operandi of voluntary cuts yielded no fruits.

This is how the Kyoto Protocol emerged in December 1997, setting the targets for reducing hydrocarbon emissions to 5.2% by 2012 based on 1990 levels (Tardi, 2020). A total of 183 member States had signed it by 2009. But Russia, Canada and Japan pulled out, while the United States and Australia declined (Skillington, 2017). It could be argued that Rio and Kyoto failed to kickstart a reversal of the climate danger because of the voluntary nature of commitments to Rio and the injustice and unequal relations between rich (dominant) countries and poor (dominated) countries. For, as Skillington (2017) posits, the refusal of historical polluting countries to bear their “differentiated” responsibility for lowering anthropogenic interferences with the earth’s climate systems, is a form of geostrategic domination.

The failure of disjointed multilateral arrangements (e.g., Rio 1992 on the environment, Beijing 1995 on women and gender and Kyoto 1997 on climate) to secure sustainable development, stimulated a movement for a more composite approach to housekeeping global development agendas. The MDGs were therefore instituted as a “shorthand set” of international development goals which could be more easily funded (McArthur, 2014). Of the eight MDGs formulated to transform the world between 2000 and 2015, climate change was a feature of the 7th goal (“Ensure Environmental Sustainability”) (see United Nations, n.d.). Kyoto, signed three years before the MDGs kicked-in in 2000, held the standards for rolling back climate change, without transformational results. Though there was a slight decrease in global deforestation from an annual loss of 8.3 million hectares in 1990 to 5.2 million hectares by 2010 (with an increase in afforestation, as well as a removal of ozone depleting substances), carbon emissions worsened. In essence, global emissions of CO2 increased by over 50% between 1990 and 2012 (United Nations, n.d.).

The gravity of the climate crisis as well as limited progress on most of the MDGs, therefore inspired the formulation of better targeted goals to complete the unfinished business of the Millennium ones for the next 15 years from 2015 to 2030. SDG 13 on “Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts”, which is crucial to realising the goal of drastically cutting GHG emissions by 2030 to reach net zero emissions by 2050, was therefore outlined (United Nations, 2015a).

So, halfway down the road to 2030, the deadline to implement SDG 13 and all others, how has the world fared with it, especially vis-à-vis climate justice? What are the factors underpinning recorded performance (from a discursive political economy worldview) and what chances are there for the Goal to transform the world with regards to the current disturbing climate puzzle? The next section responds to these queries.

III) Critical Surgery of SDG 13 and its Capacity to Transform the World’s Climate Conundrum by 2030

Considering that at the core of SDG 13 is the need to reverse climate change, which 97% of climate scientists agree is caused by GHG emissions (Klein, 2015), and in line with recent reports of the United Nations Statistics Division (2021) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2022) the world has underperformed on this objective.

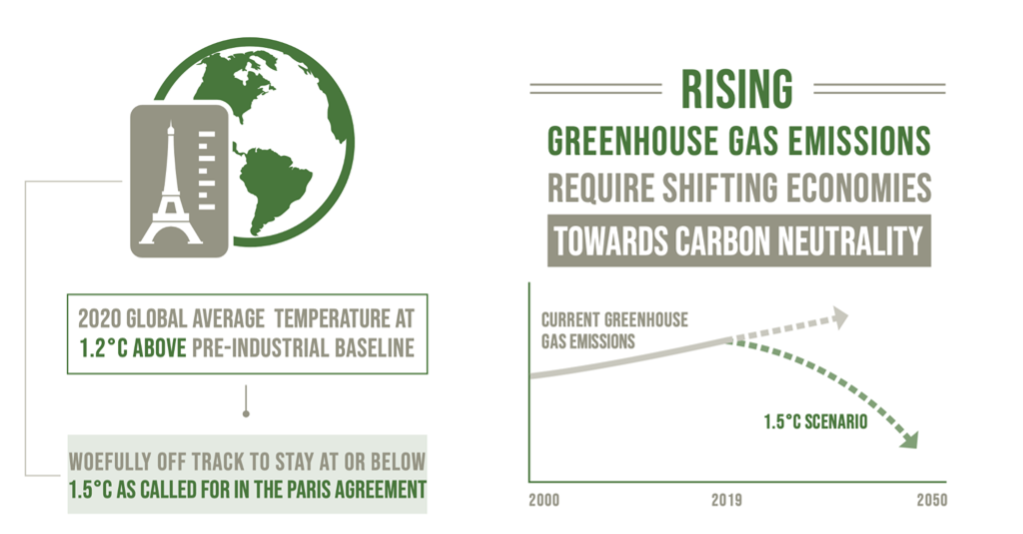

“The world remains woefully off track in meeting the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and reaching net-zero carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions globally by 2050” (United Nations Statistics Division, 2021).

Meanwhile, Working Group III’s submission of the 6th climate assessment cycle of reports by the IPCC, released in April 2022, notes that 59 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas were emitted between 2010 and 2019 and, as such, the world faces a grave danger of experiencing heating beyond 1.5°C (IPCC, 2022).

Below is a score card of the targets of SDG 13, in the context of their ability to solve the world’s climate puzzle by 2030.

III-A) Target 13.1: Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries

Indicator 13.1.1: “number of deaths, missing persons and directly affected persons attributed to disasters per 100,000 population”

Statistics for this indicator from the Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021 (United Nations Statistics Division, 2021), show a rate of 0.08 persons per hundred thousand dying from climate related disasters in 2019, down from 0.10 in 2014. The United States cut back on its disaster deaths by more than half from 0.07 persons per hundred thousand in 2014 to 0.03 in 2019. But the case in Africa worsened three-folds from 0.05 persons per hundred thousand in 2015 to 0.15 in 2019. Nepal, the world’s most affected disaster country per capita, performed five times better, reducing its death toll from 1.98 to 0.39 persons per hundred thousand in 2019.

The overall statistics show that Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean lag behind, while developed countries and Asia have improved their score cards. Nonetheless, the figures still indicate that the poor, people of colour and women bear the brunt of climate hazards as they’ve suffered historical loss of habitable spaces due to colonial occupations. This, as Stein (2004) notes, represents environmental injustice. The case is even stronger when we consider that exposure to hazardous climate events by the poorer people of Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, has been generated by industrial action, wanton destruction of the environment and unsustainable consumption patterns by rich countries and their capital-driven transnational companies. There is no sign that the disadvantaged countries would do better in avoiding climate disaster deaths by 2030, given that only recently in May 2022, more than 450 people died in KwaZulu Natal in South Africa’s worst floods in 60 years. The incident has been squarely blamed on climate change (The Guardian, 2022a; The Guardian, 2022b).

Indicator 13.1.2: Number of countries that adopt and implement national disaster risk reduction strategies in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030

Most countries in Asia including China, India and Japan, and most countries in the Global North, have adopted national risk reduction strategies in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (SDG Tracker, 2022).

The tracker reveals that only 17 African countries have finalised such strategies. Despite its Disaster Management Act since 2003 (see South African Government, n.d.) and its active participation in Sendai Framework process (COGTA, 2019), South Africa (which is Africa’s most industrialised nation) cannot cope with floods (see previous section). The problem with this indicator and others, as the United Nations in LAOPDR (2017) has rightly observed, is that they do not really measure resilience, but only the impact of disasters and availability of disaster risk reduction (DRR) strategies. Curiously, Canada with the highest per capita rate of GHG emissions (see IPCC, 2022), has not adopted any DRR policy. This vacillation, for capitalism’s sake, blinkers the view of richer countries which have engendered the problem from helping countries still struggling with bread-and-butter issues, on adaptation to climate hazards. As such, 2030 seems farfetched for the most vulnerable, to survive climate-induced disasters.

Indicator 13.1.3: Proportion of local governments that adopt and implement local disaster risk reduction strategies in line with national disaster risk reduction strategies

Southeast Asian countries and India are well on course with DRR strategies alongside Northern Europe, Western Latin America, USA and Mexico (SDG Tracker, 2022). Unfortunately, only 22 countries in Africa (less than half of the continent) are shown to have such plans. The big powers of Latin America – Brazil and Argentina – as well as Canada are shown to have none. The argument of the foregoing subsection that resilience is not based on paper plans but by the means to act, holds here. There is a tendency within the SDGs discourse to ‘count beans’ in a way that comforts the big polluters, who happen to engineer the system, due to their funding and convening pre-eminence. On the ground, the poor, coloured, women would still bear the brunt of climate-induced disasters, with no hope in sight for the nominally imposed year of 2030.

III-B) Target 13.2: Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning

Indicator 13.2.1: Number of countries with nationally determined contributions, long-term strategies, national adaptation plans and adaptation communications, as reported to the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

The United Nations Statistics Division (2021) reveals that by May 2021, 125 of 154 developing countries were in the process of formulating and implementing national climate adaptation plans in food security and production, terrestrial and wetland ecosystems, freshwater resources, human health, and key economic sectors and services. Only 22 had filed in their adaption plans. However, by May 2021, 192 Parties to the Paris Agreement, reached during the 21st session of the Conference of Parties to UNFCCC (COP 21) had submitted their first nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the UNFCCC Secretariat. Article 4, paragraph 4 of the Paris Agreement requires developed country Parties to make “economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets” and for developing country Parties to “continue enhancing their mitigation efforts” (United Nations, 2015b). How can such a laissez-faire regime on a ‘legally binding’ agreement expect to achieve results for an urgent existential threat as climate change? As earlier argued, the loose stricture of the international climate change brokering regime, engineered by the dominance of the Global North, is not a transformative solution for the world’s climate by 2030.

Indicator 13.2.2: Total greenhouse gas emissions per year

Drastically reducing GHG emissions to reach net zero (a situation where the total emissions in the atmosphere would have been removed and no more gases spewed back there), for a 50% chance to keep global warming under 1.5°C in comparison to pre-industrial epoch earth temperatures, is the leitmotif of this indicator (see The Years Project, 2019; McKinsey & Company, 2022). Unfortunately, the world has tragically failed to make progress here as indicated by the UN’s review (United Nations Statistics Division, 2021), discussed supra.

The very wording of Article 2.1 (a) of the Paris Agreement offers dominant polluting countries a blank cheque to pussyfoot on targets. It warrants action by:

Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change (United Nations, 2015b).

Climate scientists agree that the least standard to avert a catastrophic situation is to limit warming to below 1.5°C, yet the Paris Agreement itself creates room for vacillation by suggesting the pursuit of cuts under 2°C. And the big polluters have taken advantage of it! The difference between 1.5°c and 2°C of warming is huge, yet the ruling class of historically polluting countries is eroding the science with politics and the fear of losing political support from far-right owned transnational companies which profit from dirty industrialisation (The Years Project, 2019). IPCC (2022) is clear that that the global carbon budget left to remain within 1.5°C of global warming is 400 billion tonnes CO2, yet emissions are rising at breakneck speed. Paris warrants countries to make nationally determined contributions (NDCs) – a carte blanche for limited accountability. Even though IPCC (2022) calls for yearly CO2 emission reductions of at least 7% from the main polluters, the polluters have seen no urgency to act in this direction.

The updated NDC goals of China (the current lead polluter) aim to peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060; to lower CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by over 65% from the 2005 level and to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25%. While China plans to reach carbon neutrality in 2060 (10 years later than Paris warrants), it does not show in its 2021 NDC what its absolute emission cuts would be, but rather promises to cut CO2 emissions per GDP unit by over 65% (see Government of China, 2021).

The United States, the highest historical polluter, is clearer on its targets in its latest NDC – to reduce emissions by 50-52 percent below 2005 levels in 2030 (where the 2005 level was above 6 billion tonnes) (Government of USA, 2021). We see, again, that with loose rules and disjointed approaches, the richer nations, who bear the guilt for the anthropogenic causes of climate change, have not been made to critically account for their actions and to reverse them. There’s therefore no hope for the climate crisis to abate by 2030, as exhibited by infographic 1 below.

III-C) Target 13.3 improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning

Indicator 13.3.1: Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in (a) national education policies; (b) curricula; (c) teacher education; and (d) student assessment

Data tracked as of 2020 shows high global gaps on progress here. Africa is the worst performer with only four countries (Algeria, Burkina Faso, DRC and Mozambique) identified as implementers. Many countries of the Global North (including Australia, USA, the UK, Sweden, Norway and Japan) and most of Asia (including powerhouses as China, Indonesia and Singapore) are not shown to have taken action either. This indicates that apart from the experts of the field, the world is still asleep on seriously acting to avoid a climate calamity. There can be no miracle by 2030.

III-D) Target 13.a: Implement the commitment undertaken by developed- country Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to a goal of mobilising jointly $100 billion annually by 2020 from all sources to address the needs of developing countries in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation and fully operationalise the green climate fund through its capitalisation as soon as possible

Indicator 13.a.1: Amounts provided and mobilised in United States dollars per year in relation to the continued existing collective mobilisation goal of the $100 billion commitment through to 2025

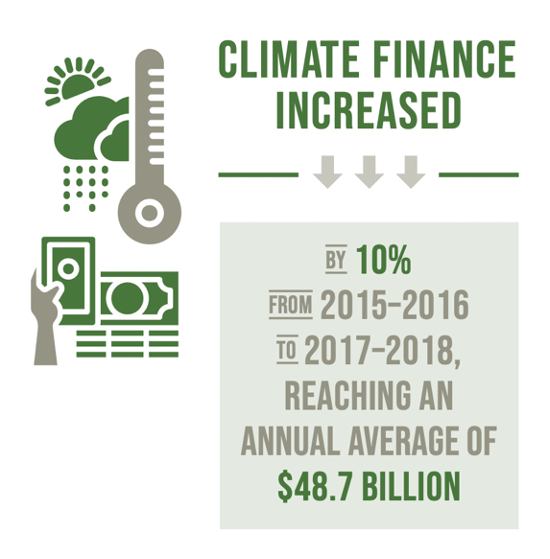

Climate financing has not been optimal. The United Nations Statistics Division (2021) indicated that climate finance increased by 10% from 2015–2016 to 2017–2018 (see infographic 2), reaching an annual average of $48.7 billion. This was a good sign before 2020. However, the Green Climate Fund (2022) – has indicated that resources under its portfolio as well as co-financing was a mere $37 billion in 2021. According to McKinsey & Company (2022), the world would need $275 trillion to finance the transition to carbon-free energy from 2021 to 2050. This translates into an annual need of $9.2 trillion each year. The amount of $100 billion which reach countries have failed to fork out as promised, is a paltry 1.08% of the global needs. At this rate, working towards climate change reversal by 2030 remains a pipe dream. The slowness in pursuing promises to ease the effects of climate change on poorer countries, on whom the injustice of pollution has been imposed, further entrenches the existing spatial inequalities borne of a discourse of imaginative geographies (see Dawson, 2013) in terms of a response to a problem that has been orchestrated by the more powerful. Imaginative geographies translate here as a system of otherness in which the Global South bears the brunt of climate change largely orchestrated by the Global North, but for which the latter pays little or no heed.

III-E) Target 13.b: Promote mechanisms for raising capacity for effective climate change-related planning and management in least developed countries and small island developing states, including focusing on women, youth and local and marginalised communities

Indicator 13.b.1: Number of least developed countries and small island developing States with nationally determined contributions, long-term strategies, national adaptation plans and adaptation communications, as reported to the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

According to the Bond Development and Environment Group (2019), only an estimated $9 billion of annual public climate finance went to the world’s 48 least developed countries (LDCs) in 2015-16, representing just 18% of the total pot. LDCs and small island developing states (SIDS) need far more support as they are estimated to have respectively contributed only 3.3% and 0.6% of global GHG emissions in 2019 (IPCC, 2022). With such limited support, there might be even more ominous days for them ahead of 2030 with the trend of extreme weather events to which they are most vulnerable and exposed.

IV) CONCLUSION

SDG 13, as we have seen, is a central thrust of the UN’s Agenda 2030. It would have been a lofty Goal to help transform the world by 2030 but it is beset by issues. First, the political economy of the combat against climate change is skewed to the comfort of powerful polluting nations who are under the spell of more powerful far-right capitalists involved in the profiteering from brown economic production. Targets are open-ended, hence commitment to reducing emissions is frail. Financing adaptation and mitigation processes in poorer nations, which have been less of the problem but more of the solution given their carbon-sucking ecologies, is seen as charity rather than responsibility. The global ecosystem to reverse climate change is a terrain where inequality among nations, races, gender and classes is accentuated, putting the world on a dangerous climate trajectory. Till these structures are overhauled, 2030 would not be the magic year for transformation. If anything, the climate conundrum may only get worse.

Good to know.